Good reading from CHINA POLICY

Philippa

Backbone of its R&D capability, the PRC’s state laboratories play pivotal roles in advancing basic research, driving tech innovation, and realising national priorities. State labs sit in two tiers: National Labs on top and National Key Labs (NKLs) below. Each tier serves a distinct purpose within the R&D ecosystem.

In this survey, we break down the hierarchy of state labs, their functions, funding mechanisms, and recent makeovers updating them for the new era.

national labs (国家实验室)

National Labs are the peak bodies of PRC research infrastructure, tackling such broad, critical fields as nuclear physics. Typically sited on large campuses, they employ hundreds or even thousands of researchers and use cutting-edge, large-scale equipment.

NSRL, Hefei, Anhui province

The first National Lab, NSRL (National Synchrotron Radiation Lab), was set up in 1984. Its centrepiece is a synchrotron, generating intense beams of light (synchrotron radiation). Tuned to different wavelengths, these beams allow the structure and properties of materials to be probed with high precision.

Recent breakthroughs at NSRL include

ammonia synthesis: working with Jilin University and Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, mild conditions for ammonia synthesis—key for fertiliser production—were found, potentially raising efficiency

overcoming tumour drug resistance: teams at the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering used NSRL facilities to overcome resistance using magneto-mechanical therapy combined with chemotherapy. Magnetic fields can raise the effectiveness of treatment

catalyst identification: real-time observation of chemical reactions is achieved at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) using NSRL techniques to identify catalytic active sites. More effective catalysts for energy and environmental applications are in view

These are examples of National Labs acting as platforms, allowing the broader research community to make strides.

While National Labs primarily focus on basic research, they are also designed to support long-term industrial innovation. Emerging industries, such as quantum communications, are deeply tied to advances in fundamental science.

building out national labs

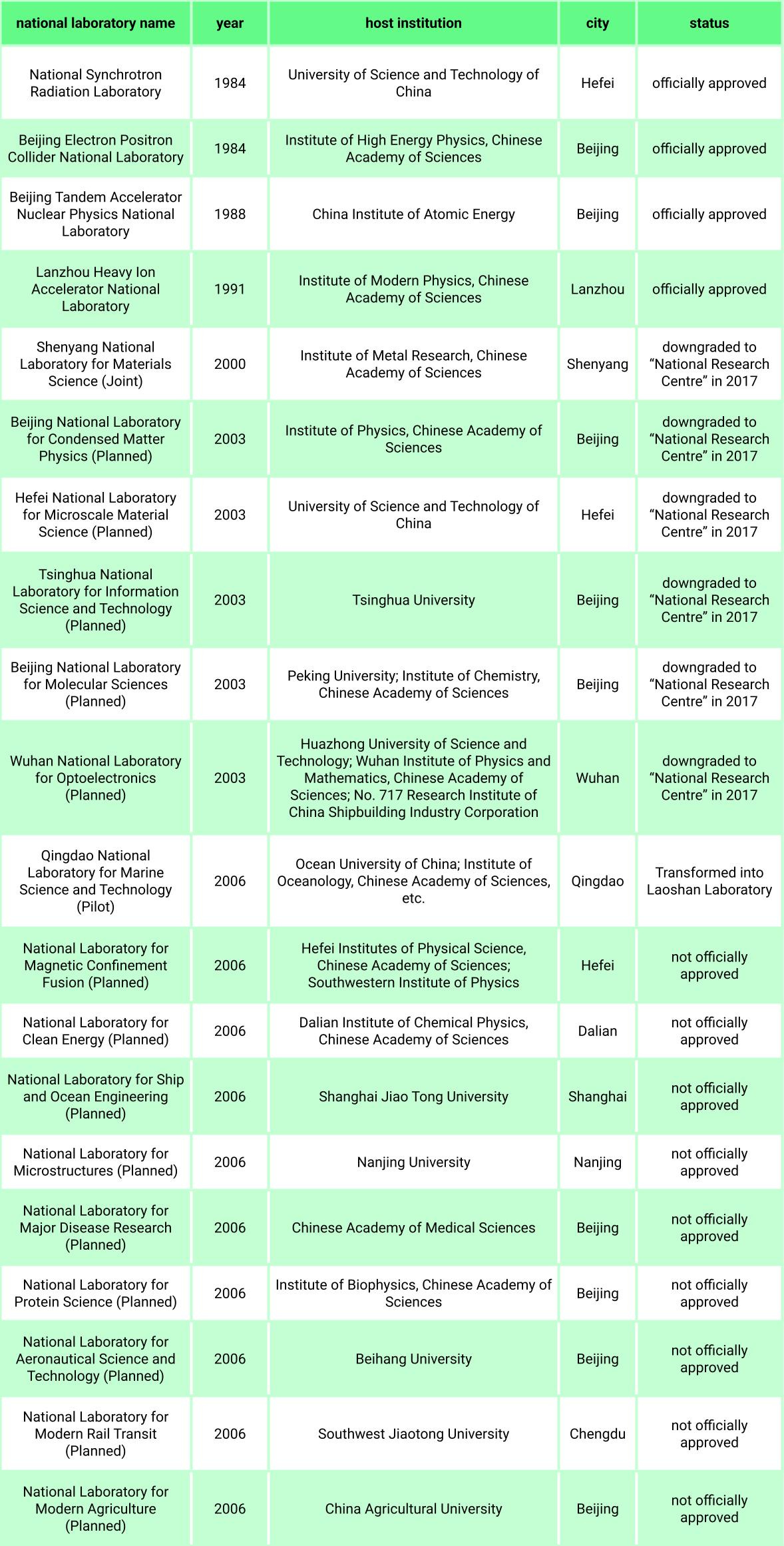

Only four National Labs have been approved to date, marking their elite status. Sixteen more were proposed 2000–06, but due to unclear evaluation standards, they remained in the chóu 筹 (preparatory) stage for over a decade.

This uncertainty hampered the research sector. Hence, this approach was reevaluated in 2017. Six labs in the preparation phase were downgraded to National Research Centres (国家研究中心). Labs left in the chóu stage have yet to—may indeed never—receive approval.

new national labs in the making?

Grudging approval of planned National Labs suggests misalignment with rapidly evolving state priorities. Relegation to National Research Centre status or outright disqualification suggests reallocating resources to emerging, cutting-edge fields.

The 14th 5-year plan (2021) confirmed this, envisioning new National Labs in such areas as AI, quantum technology, biomedicine, and network communications. Local governments have since launched several labs claiming National Lab status.

Yet Beijing has not officially confirmed this status. Labs with overlapping research missions (e.g., Zhijiang and Pujiang Labs, both for AI) appear to be rivals for central approval.

Naming conventions hint at a new trend, typically identifying districts in the host cities (a classic case being Zhongguancun 中关村 in Beijing). Thus, the researchers' specific focus is obscured.

national key labs (全国重点实验室)

NKLs sit at the level below National Laboratories and National Research Centres in the research hierarchy. In the most significant move since the 1980s, the Politburo approved a plan in 2021 to restructure and further cull SKLs (State Key Labs 国家重点实验室)

all had to reapply for the newly minted ‘National’ status between 2022–24. The previous State Key Lab system was replaced with the term National Key Labs (全国重点实验室), signalling a shift in priorities.

NKLs are more narrowly specialised than National Laboratories. Universities or CAS institutes primarily host them, though a few are housed in enterprises.

NKLs receive less central government funding than National Labs. In 2019, support and equipment upgrades for NKLs totaled C¥64 bn. Host campuses or institutes must provide consistent support, including space, staffing, and research funding worth at least C¥500K annually.

Most funding, however, comes from competitive grants. NKLs enjoy preferential access to national scitech grants.

NKL reform (2022–24)

Targeting inefficiency, reform of SKLs brewed for nearly a decade. MoST noted ‘a paucity of groundbreaking results, lack of top-tier scientists, and outdated management systems’ in 2018.

The number of SKLs was initially set to expand to 700 by 2020. By then, however, barely 500 were operating. A shift in thinking prioritised quality over quantity, reacting against overlapping missions, resource misallocation, and ill-fit with national priorities.

The 2022–24 restructuring included rigorous re-evaluation to determine which labs would qualify under the new framework. To reapply entailed proving strategic alignment and problem-solving capability. Labs were required to answer

what were the major scitech challenges facing the PRC?

which of these did the lab address?

what unique, irreplaceable capabilities did it provide?

Labs falling short of these standards lost funding, and their SKL status became moot. ‘Fewer but stronger’ labs was the watchword, spelled out by then MoST minister Wang Zhigang 王志刚. NKLs were now to focus on a single, high-priority, nationally important scientific issue rather than broad or abstract scholarship.

The research pendulum having swung from ‘pure’ back to ‘applied’, the makeover blurs divisions of labour between NKLs and National Engineering Centres (国家工程研究中心), which are dedicated to applied research and prototyping. While NKLs report to MoST, Engineering Centres answer to the NDRC, creating potential overlaps and inefficiencies despite coordination efforts by the Central Science and Technology Commission.

winners and losers

The number of university-affiliated labs fell from some 300 SKLs to 254 NKLs. The most labs are at Tsinghua, Zhejiang, China Agricultural, Shanghai Jiaotong, and Peking universities.

China Agricultural U. was a big winner, leaping from below the top 10 for SKLs to a leading position. Reputedly strong universities like Fudan and Nanjing underperformed.

Most NKLs evolved from existing SKLs, but the reform allowed new entrants. For example, previously lacking any SKLs, Henan Normal University gained NKL recognition in 2023 for its antiviral drug discovery lab.

everyone on board?

basic research advocate: Zhou Zhonghe 周忠和 | CPPCC member and China Association for Science and Popularisation president

State labs should keep focusing on basic research, argues Zhou. Labs will struggle to advance cutting-edge basic research when under administrative pressure to address national needs within a few years. Overemphasis on practical results could undermine labs’ ability to conduct fundamental, curiosity-driven research.

He highlights the need for university-affiliated labs to differentiate themselves from enterprise-hosted and ministry-affiliated labs, focusing on basic research instead of applied innovation. While applying for NKL status, labs had to choose between categories—basic research, applied basic research, or cutting-edge technology—raising speculation about whether such differentiated evaluation criteria may already be standard practice.

Zhou, a leading paleontologist and science communicator, earned his PhD from the University of Kansas in 1999. He became a CAS academician in 2011 and director of the CAS Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology. As a CPPCC member, he has consistently urged basic science funding reforms and the nurturing of scientific curiosity.

applied research advocate: Sun Ninghui 孙凝晖 | Chinese Academy of Engineering academician

Sun champions top-down labs aligned with national priorities. Under the ‘new nationwide system’, they must deliver tech breakthroughs rather than focus on pointless metrics such as numbers of academic publications.

His proposals go a step further than the current reforms. In addition to reformed national labs, he urges a 'team of strategic scientist' to deal with critical bottleneck technologies, coordinating efforts across National Labs and NKLs.

Sun Ninghui’s vision for the lab system

A member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, Sun is a high-performance computer scientist and director of the State Key Laboratory of Computer Architecture. A key policy advisor on AI and computing, he advises senior policymakers and leads national research initiatives.