A warm welcome to the next post in our Third Plenum series. We now look in more detail at scitech—the Holy Grail of the New Era. First, we unpack the new top-down plans. In our next post, we will ponder the bottom-up arrangements.

Philippa

Under General Secretary Xi’s ‘new development pattern’, as noted in a previous post, the PRC is pursuing the scitech high frontier, pivoting away from Deng-era pro-market policy and ‘hide and bide’ approaches.

Frustrated with advanced states safeguarding their cutting-edge scitech, Beijing has lost faith in its ability to source technology from global markets. Thirty ‘chokehold’ technologies were identified by state media in 2018. Beijing frames this strategic deficit as an existential threat.

This imperative is hammered home in the policy realm through calls for ‘self-reliance’. Rectifying bottlenecks in present technology is all very well, but ambition is also to be nurtured for future technologies. In 2023, Beijing identifies

eight emerging industries where the PRC has been proactive for years and now believes it can compete for a leading position

new IT (5G, AI, cloud computing, big data)

new energy

new materials

high-end equipment

new energy vehicles

green environmental protection

civil aviation

ship and marine engineering equipment

nine future industries where leadership is still up for grabs

metaverse

brain-computer interface tech

quantum information

humanoid robots

generative AI

biomanufacturing

future screen displays

future networks

new energy storage

structural shortcomings

How does the PRC set itself up to break through and become a leading innovator? With the arrival of the ‘New Era’, Beijing overhauled state agencies in 2018 and pump-primed its aspirations for an ‘innovation’-driven state.

But with a raft of structural shortcomings, the pump-priming failed in critical aspects. A case in point was the corruption scandal infecting the IC Big Fund in 2022 that temporarily derailed the PRC chip initiative.

nationwide system takes shape

A ‘new nationwide system’ (新型举国体制) is now heralded as the panacea. It aims to bolster the central role of the Party-state to set priorities and guide the allocation of resources like talent, equipment, and funding.

At the apex is the Central Science and Technology Commission, launched in early 2023. It held its first meeting, behind closed doors with no public read-out, in July. The public learned of it only in August: a low-level Party branch within the Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) inadvertently referred to ‘studying the spirit’ of the meeting.

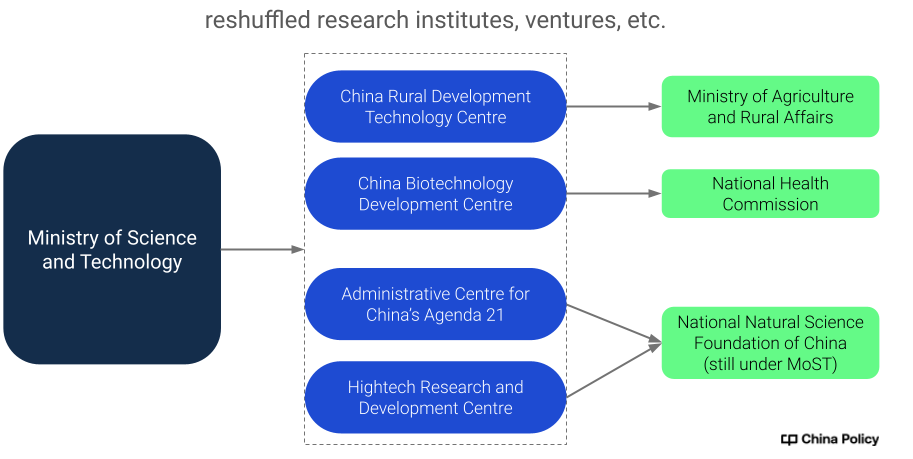

A related state agency overhaul (see charts) is repositioning MoST. As an executor of Commission policy, it loses its funding remit assuming a guiding, not a practical, role. Functions and personnel will transfer to other agencies. Full national roll-out will be seen by early 2024, at the local level by late that year.

echoing the past

The ‘new nationwide system’ reinvents an earlier ‘nationwide system’ that emerged after the Sino-Soviet split, when the PRC lost Soviet patronage of its nuclear weapons program. A ‘Special Central Commission’ led by Zhou Enlai 周恩来 ensured strategic focus, bundled and coordinated resources and forestalled local rent-seeking.

Reviving this faith in doing ‘big and great things’ is also inherent in the new nationwide system.

Yet the ‘new system' is no return to the Mao-era command economy, were that even feasible. Its calamitous inefficiency was seared into the minds of a generation of Party economic cadres. The reform era has been, among other things, a crash course in efficiency.

The new system draws from both previous regimes as shown in the table below.

getting there from here

The internal workings of the Central Science and Technology Commission remain hazy. Even less clear are the bottom-up arrangements of the new system.

How exactly to involve industry stakeholders, the research community, and international partners in decentralised competition? We will delve into this in our next post.